Wastewater treatment removes various pollutants that can harm natural ecosystems and pose risks to human health. These pollutants include solids, dissolved organic compounds, nutrients, and pathogenic organisms. Solid pollutants come in different forms, such as human-made objects (rags, plastics), inorganic materials (silt, clay, sand), and organic matter (decaying plants and animals, feces). Dissolved organics consist of compounds from decaying biological material that do not settle like solids. Nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, enter wastewater from sources like urine, feces, and synthetic products. Pathogenic organisms, which can cause disease, often thrive in untreated wastewater. At high concentrations, all of these pollutants can be damaging to both people and the environment.

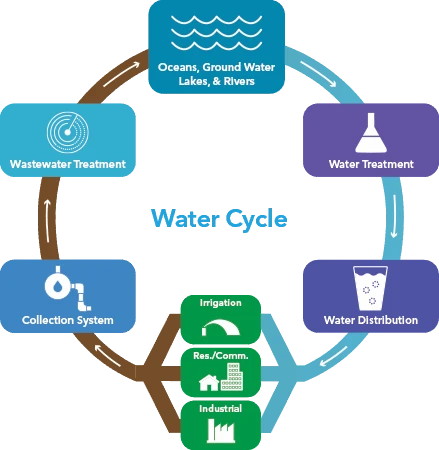

The Water Cycle: Human use of water follows a continuous cycle. Water is drawn from various sources such as lakes, rivers, and groundwater. Before it reaches homes, businesses, and industries, it undergoes treatment to meet safety standards for consumption. Once used, the water becomes wastewater, which must be treated again to remove harmful contaminants. After this treatment, the clean water is safely discharged back into the environment, completing the cycle.

Before wastewater effluent is discharged into streams, estuaries, or other receiving waters, it must comply with standards set by the National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). Established by the EPA under the Clean Water Act of 1972, the NPDES issues permits that specify the allowable pollutant levels for each facility based on the needs of the receiving water body. The Clean Water Act also set water quality standards for surface waters, provided protections against industrial and municipal waste, and funded the development of advanced wastewater treatment technologies. While wastewater management has a long history, the Clean Water Act marked a major turning point in reducing the impact of human activity on waterways and enhancing the health of natural ecosystems.

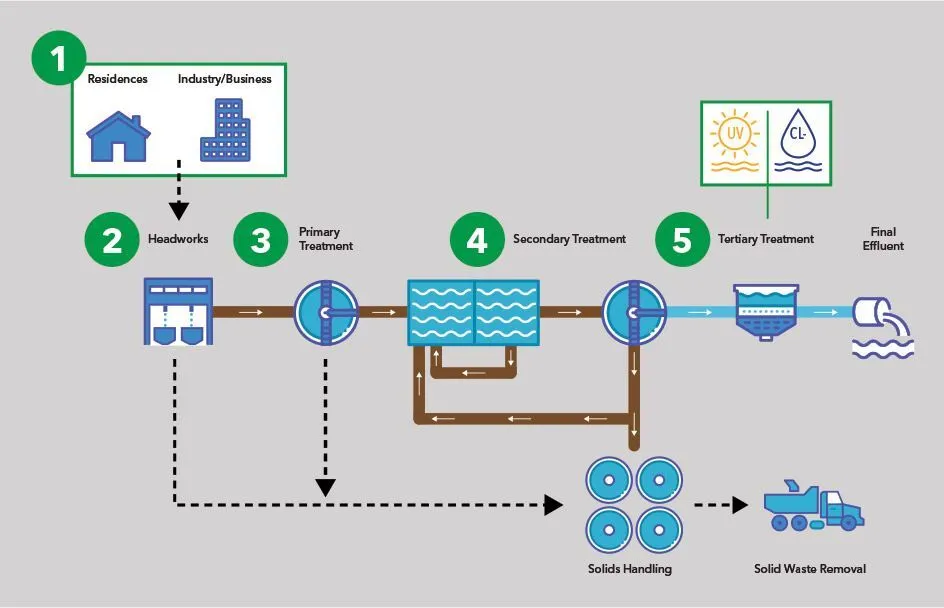

All waste generated by society—such as garbage and recyclable materials—is collected and managed through various processes to protect the environment. Wastewater is handled in a similar way. A wastewater collection system consists of pipes and lift stations that transport used water from homes, businesses, and industries to a treatment facility. Civil engineers design these systems to rely primarily on gravity, using natural slopes to move water efficiently. However, lift stations are strategically placed in some areas to pump water to higher elevations and maintain flow. Depending on the design, municipalities may use sanitary sewer systems, which carry only wastewater, or combined sewer systems, which collect both stormwater and wastewater. Combined systems often present additional challenges, such as managing high flow volumes during storms.

The collection system brings wastewater to the beginning of the treatment facility, also known as the headworks. The headworks are responsible for removing large debris and heavy solids from the water, such as wood, rags, plastics, sand, gravel, grease, and personal hygiene products. This stage prepares the wastewater for the downstream stages by removing solids that may damage pumps and other equipment. Specialized pumps bring raw wastewater from influent wells up to a series of bar screens and grit removal chambers. These two common pieces of equipment will help remove a portion of the incoming solids (total suspended solids, TSS) and organic material (biochemical oxygen demand, BOD). Sensors for TSS, TDS (total dissolved solids), turbidity, and pH can be used to monitor incoming wastewater for EPA violations and loads that may be dangerous to downstream biological processes.

After the larger debris is removed, the organic and inorganic solids can be removed in a process called primary treatment, reducing influent BOD by 25-40% and influent TSS by 50-70%. Circular or rectangular clarifiers are most often used to separate solids from the water via gravity separation. The speed of flow in these tanks allows solids to settle at the bottom of the tank to form sludge, which is then pumped to another section of the treatment facility for biosolids treatment. The separated water then flows over the weirs at the surface of the clarifiers and onto the next treatment step. The biosolids collected from both primary and secondary treatment are collected, reduced in volume, and then either disposed of or created into fertilizers. Before the Clean Water Act, many wastewater treatments plants only utilized primary treatment. However, secondary treatment has become a requirement with the increase in industry and city population.

With endless tank configurations and the utilization of live microorganisms, secondary treatment is perhaps the most complex stage of wastewater treatment. In this stage, dissolved pollutants like organic matter or nutrients are removed using the biological processes of certain microorganisms (bacteria, protozoa, etc.). Different environments can be created within large tanks with high solids (i.e., activated sludge basins) to accumulate the desired type of microorganism. Aeration is added to some tanks to provide oxygen and grow bacteria which remove organics and ammonia, while aeration can be purposefully limited to assist with nitrogen or phosphorus removal. The number and order of these tanks are configured to meet goals specific to the facility. After the activated sludge basins, another set of clarifiers is used to separate the activated solids from the water via secondary clarification.

This location utilizes the most online sensors to monitor the activated sludge system. Sensors for DO (dissolved oxygen), TSS, ammonium, nitrate, ORP (oxidation-reduction potential), pH, and orthophosphate monitor the conditions within each tank. Whether the environment is aerobic (oxygen-rich), anoxic (low oxygen, nitrate available), or anaerobic (no oxygen, no nitrate), these parameters are maintained at optimum levels. In addition, sensors are used to automatically control pumps, aeration, and chemical dosing. DO and ammonium sensors can control aeration to provide precise treatment. Similarly, online measurements of TSS, nitrate, and orthophosphate are used to control pumps and chemical dosing to assist with solids control and nutrient removal. Carbon parameters, such as BOD, COD, and TOC are commonly monitored as they are quantifications of the organic material in wastewater. BOD (biochemical oxygen demand) is the current NPDES standard for this measurement, however, COD (chemical oxygen demand) and TOC (total organic carbon) can be substituted for BOD, if a long-term correlation with BOD (COD:BOD or TOC:BOD) has been established.

At this point, solids and dissolved pollutants are mostly removed from the water. However, a final treatment step called tertiary treatment can include several processes to disinfect the water or further remove pollutants to achieve very stringent treatment goals. Depending on the body of water, wastewater facilities may have strict discharge limits to further protect the body of water. For example, discharge limits near freshwater lakes have very low total phosphorus (TP) limits to limit eutrophication in freshwater systems, while coastal wastewater facilities will have low total nitrogen (TN) limits in a saltwater system.

Disinfection is an important step to kill or deactivate pathogenic organisms before they return to the environment. Chlorine and UV disinfection are the most common methods, both of which damage the cell walls and eliminate the ability of pathogens to reproduce. Chlorine disinfection has been used for decades to disinfect wastewater. Many forms of chlorine can be dosed at the beginning of contact tanks, providing enough time for the chlorine to kill bacteria and dissipate or dechlorinate before the final effluent. Chlorine analyzers monitor chlorine levels after the contact tanks to ensure enough chlorine is dosed, but also to ensure low amounts of chorine are discharged. UV disinfection systems are becoming more prevalent as they do not require storing and dosing hazardous chlorine chemicals. UV banks emit light in a series of channels to deactivate bacteria before discharge. UVT% sensors can control the UV banks to dose the exact amount of light required to achieve the required disinfection.

Tertiary treatment can also include another filtration step utilizing processes like sand filtration, membrane filters, or disk filters, which can remove solids and, thus, other pollutants down to extremely low levels.

AG-CMn07 permanganate index water quality online automatic monitoring instrument

See Details

AG-DC07 five parameter (pH, turbidity, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, temperature) water quality online automatic monitoring instrument

See Details

AG-NH07 Ammonia Escape Online Monitoring System

See Details

WAPM-DC103 portable multi parameter detector

See Details